A generation after the battles that settled the future of the continent of Kantos, the fighting forces at the Êstâz's command were divided into six armies. First Army was the Army of Elarâń, defending the core of the Kingdom if all others failed. Second Army was the Army of Gir, watching over the nomads as they roamed the grasslands with their herds of riding animals. Farther west, the Army of Cunda, Third Army, occupied the enemy heartland. Fourth Army, in the north, made sure the High Tlâń accepted the Êstâz's rule. Fifth Army was the Army of Anθorâń, native to that city-state, the softest duty next to First Army.

Sixth Army was Frontier Command. Established just before the disastrous expedtion to Loraon, it had no well-defined populace to watch or to protect, no well-known area to patrol. Its mission was to learn what lay south of the Road of Wolves, who lived there, and whether they posed a threat or offered an opportunity to the Tlâń Kingdom, as the Êstâz's realm was increasingly being called.

Command headquarters was set up quite deliberately in the middle of nowhere, just beyond the borders of the Kingdom. Due east lay the Wastes where nothing lived; north was Gir Province; northeast, the Peril Gate where the Dukes of Sitašai had spent so much blood defending Elarâń; south and west, with a lot of nothing between, lay the city-state of Anθorâń. But everywhere south of the curve framed by the Wastes, Gir, Cunda, and Anθorâń, the maps were empty. It was Sixth Army's job to fill them in.

The waiting room at Sixth-Army headquarters was always full of young, ambitious officers eager for the opportunity to prove themselves. Those who wished for a posting at a royal court applied to First Army or Fifth; those who sought the knife-in-the-back challenge of garrison duty among a hostile populace, Third or Fourth; while those who found the outdoor life attractive could look forward to lots of mounted patrols through Gir with Second Army. But the call of the unknown kept Sixth-Army HQ busy.

The man who stood at one of the windows that reached from floor to ceiling at intervals down the long hall was dressed in the same uniform as the other officers present, a dark blue tunic of loose cut whose flaring sleeves ended halfway between shoulders and elbows, and whose skirt hung to his knees. Under the tunic a medium grey shirt was visible where its arms hung to his elbows, and its skirt to mid shin. A white robe under the shirt had arms that ended at his wrists, and a skirt that hung to the insteps of his black leather boots. The belt around his waist held a large pouch and a knife in a sheath; the belt, pouch, and sheath were also the uniform black leather.

No uniform, however, could keep Saru son of Peta from standing out from the other officers. For one thing, he was the only Girē in the room. There were perhaps sixty officers sitting, standing, or walking around the hall, some talking in quiet voices, some reading letters, journals, or even books, some staring out the windows or staring at nothing, deep in thought. About forty of them were Râńē, men of Elarâń, six to six and a half feet tall, not counting the tendrils which rose from their temples and added another half a head to their height. Their hair was mostly brown, dark or light or medium, their eyes were mostly brown as well. The other twenty were Anθorâńē. The people from that city-state tended to be tall (six and a half or even seven feet), very slim, with tendrils rising a full head above their light brown, grey, or white hair. Their eyes were blue or an indeterminate grey as often as brown.

But Saru was a typical Girē; five and a half feet tall, with legs and arms shorter in proportion than a Râńē, a stocky torso, and tendrils that stood only a couple of inches higher than his head. The hair on that head was fiery red and curly, his skin so pale it was almost white, and his eyes a brilliant blue.

Besides being of a different physical type than anyone else in the waiting room, Saru also had the dubious distinction of holding the lowest rank present. Most of the other men wore the gold arrowhead of a tribune on both tunic sleeves, signifying command of a regiment. There were also some proconsuls bearing swords on each sleeve, and a few consuls, with the crossed swords, hoping for an Army command or a staff position. But Saru wore the plain gold stripe of a cornet, commanding only a platoon of twenty men. To see a cornet in the waiting room was more unusual than seeing a consul, and to an army man made him stand out as much as his Girē heritage.

Saru was also the oldest person in the hall, relative to his rank. The other men his age were tribunes, two ranks higher than cornet, or even proconsuls if they were lucky or precocious. Saru had been a banneret, a common soldier in charge of a banner of eighty men, at the start of the Loraon Expedition. When it returned to Kantos, the Êstâz Vîd́a made him a cornet, though he did not knight him. Now, instead of taking orders from a legate and his staff of cornets, and overseeing four platoons and their sergeants, Saru commanded a platoon of his own.

The platoon was currently unassigned, but that didn't explain what he was doing here, Saru thought. The normal way for a cornet to learn about his next assignment was for a messenger to bring him written orders. Summoning him to Army headquarters, instead, was like being ordered to attend court. Save a king's life, he thought morosely, and have your own life screwed up forever.

As his musings circled back to that point for perhaps the thousandth time that morning, the inner door of the waiting room opened. All the heads in the room turned towards the senior guardian who entered, marked as such by the two gold stars on his sleeves. Unperturbed, the high-ranking commoner called, "Cornet Saru Peta's son?"

"Here I am," Saru said, making his way to the door. Every eye was on him, some resenting that a cornet was called before they were, some because of his name. It was a known name in the army, the name of a survivor of the Loraon holocaust, who had the Êstâz's favor.

"Please come with me, sir," the senior guardian said, holding the door for Saru. Once it had shut out all the staring eyes, he led the way down a hall with six doors on either side, including the one they'd just used. None of them were marked. He knocked on the far door on the opposite side of the hall.

"Come in," called a voice.

"The cornet, Your Grace."

"Thank you, senior guardian."

As the unknighted soldier withdrew, Saru marched in, stopped directly before the big wooden desk inside, and came to attention without saluting—Êstâz's army didn't salute indoors. "Cornet Saru Peta's son, reporting as ordered, sir!"

"At ease, cornet," the man behind the desk said, which gave Saru the chance to take a quick look around the office.

It was a large office, twenty feet deep by thirty wide, but a working office, not just for show. Two wooden file cabinets, four drawers tall, stood in the far left corner; full book cases, man high, centered every wall except the one behind the desk, where a window gave light and displaced the book case to the right. A wooden frame at eye level between the window and book case held a large parchment under glass, with four large wax seals dangling beneath on blue ribbons and protected by brass seal cases.

The man behind the desk wore the crossed gold swords of a proconsul on either sleeve, and no other mark of rank. Despite his ordinary Râńē appearance, the senior guardian's form of address told Saru that the proconsul was entitled to a count's or duke's crown, though it wasn't customary wear in an ordinary army working day. If his personal banner had been displayed on a wall, it might say which he was, if the vexillographer had chosen to use a form of crown that was specific to a count, or to a duke. But the banner was neatly furled in a stand to the right of the door, and wasn't helpful.

The other person in the room, sitting in a chair half-turned to the desk and half to the door, was someone Saru knew. His tunic was bright red, and since he was a civilian it had no rank insignia on its sleeves. An orkē-head brooch in gold, with emerald eyes, was pinned below the neck of the tunic, and a heavy gold chain supported the medallion of the Order of the Phoenix, given by the Royal Academy of the Sciences for distinction. The white belt around his waist matched the white shirt under his tunic, and the cloth pouch on the belt repeated the floral pattern of the bands at the ends of the shirts's sleeves and hem. The brown robe next to his skin was the same color as his hair, his eyes, and the sheathes of the dagger and recorder on his belt. Only the boots on his feet were uniform, being the same black leather as anyone's in the army.

As Saru saw him and smiled, the civilian smiled back and stood up. Though he was plainly Râńē, he was as tall as an Anθorâńē, and nearly as slender. At six feet eight inches, he was over a foot taller than Saru. He held out a hand and said, "Hello, Saru. How have you been?"

Saru's hand disappeared in the other's grip. "Fine, Master Ĵetao, fine. I have fewer men now to ride herd on, but they're mine, not some officer's. I'm the officer now, Powergiver help us all!"

Ĵetao Juho, Doctor of the Royal Academy of the Sciences, and Master of the Phoenix, released his friend's hand. "I trust our half-Cundē friend is still with you?" he asked.

"Can't chase him off with a stick," Saru grinned. "Sergeant Paran will be pleased to hear you were asking about him."

The man in whose office they were holding their reunion coughed politely.

"I beg pardon, Your Grace!" Master Ĵetao cried. "Old friends, you know. Saru, this is Count Persu, the proconsul in charge of intelligence for Sixth Army. He and I have been discussing an expedition to the far south."

Laughing at the way Master Ĵetao had torn military protocol to shreds, all unwittingly, the count stood up and came around the desk. He was also taller than Saru, though still a couple of inches shorter than Juho.

"Be at ease, cornet," the proconsul said, holding out his hand. He had keen eyes, at the moment full of merriment. "I gather he's always like this?"

"Pretty much, sir," Saru said. As he took the hand offered, he was thinking that if Paran had said he'd be shaking the hand of a proconsul today, he'd have laughed in the sergeant's face. "If he can't dissect it, translate it, or unscrew it, Juho generally ignores it," the cornet said.

"I'd resent that if all the experimental evidence didn't back you up," Master Ĵetao said. He picked up something from the corner of the desk by his chair. "Take a look at this," he said, handing it to Saru.

Saru turned it over in his hands while the doctor and the count watched him. It appeared to be black silk, about four feet wide, rolled up in a bundle a couple of inches in diameter, tied with a leather lace around the middle. He hefted it in one hand. It was heavier than he expected, but…

"What is it?" he asked.

"Untie it and see," said Count Persu.

Saru deftly untied the leather lace, thrust it through his belt, and began unrolling the fabric in both hands. It was only black on one side, he saw. On the other—

"What in the world?" he exclaimed.

Unrolled, the material he'd mistaken for cloth was roughly four feet wide by about five and a half feet tall, Saru's own height. The edges were rough, as if someone had cut it out of a larger piece with a knife. He struggled to make sense of what he was seeing. Centered on the material was an irregular white blob surrounded by blue. Superimposed on the white and the blue were a number of glowing yellow ovals of different sizes and orientations that mostly didn't overlap. On each glowing yellow oval was a glowing yellow dot. Writing in the old alphabet, which Saru had never learned, appeared here and there.

"What am I looking at?" Saru said.

"Would you believe a kind of map?" Doctor Ĵetao said.

"Huh?" Saru answered brilliantly.

"Bring it over here, cornet," Count Persu said. He led the way to the bookcase beside the window. The book cases were a uniform six feet tall and four feet wide. The count took the sheet of material from Saru while the doctor removed several heavy books from the book case. Together they hung the picture by placing the books on its top inch, letting it dangle with its bottom edge half a foot from the floor.

"There," said Master Ĵetao. "That will do for now."

"Very neat," Saru said. "But it still makes no sense to me."

"Well," said the doctor, "suppose I hold one arm up in front of it, thus; and another arm straight out, like so. Look in the upper-right area framed by my arms. Does anything look familiar?"

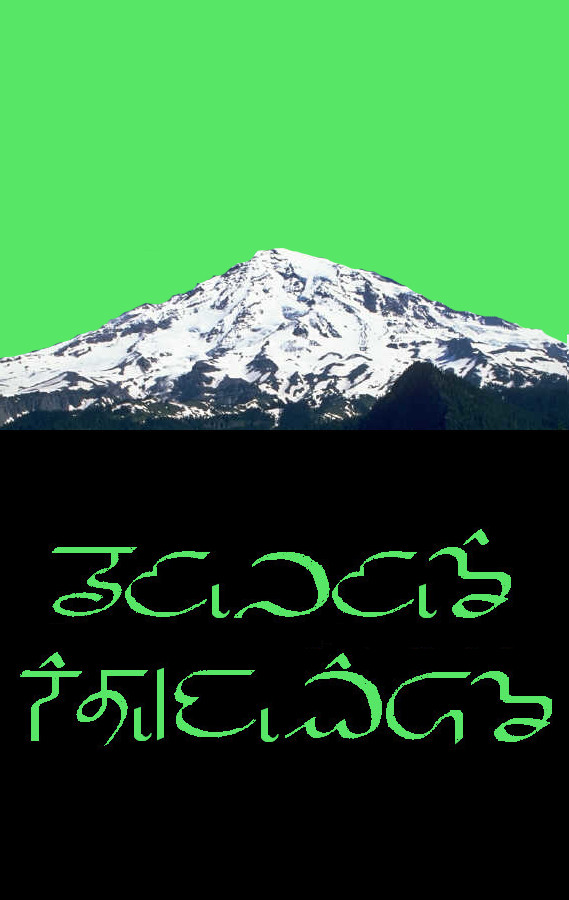

Saru looked for a moment; and then, as the doctor was about to speak again, it suddenly leapt out at him. "Elarâń?" he said. He stepped closer, and peered up at it. Master Ĵetao dropped his arms as Saru reached up with his right hand.

"Yes," the cornet said. "If you ignore the glowing circles… the western arm of the Sealed Mountains would run along here, and the southern arm here, the Wastes would be here, Gir there, Cunda there, Anθorâń—this is like a map of Kantos in outline, without mountains, rivers, or anything—isn't it?"

"It is indeed," said His Grace. "And see how much of the continent we know nothing about. There's easily three or four times as much land south of us as all the present kingdom put together, and all of it unknown."

"So you believe this is accurate, sir?" Saru said.

"It's accurate," Juho said. "After we got back from Loraon, I went to Tlâńor, to see what the Library there had on Loraonai flora and fauna, to compare with my own notes. I had a tough time getting access to their records. Some High Tlâń still resent the loss or failure of their self-imposed duty to save the world, and won't have anything to do with outsiders."

"Some of them do worse than just shut out the world," Count Persu commented. "There are places our patrols dare not go except in strength."

"Yes, yes," said Master Ĵetao, waving one long hand. "But I'm not in the army, and the younger High Tlâń are happy to be free of their parents' burden. A lot of them turn to science as a way to explore the world free of political considerations, where joining the army, for instance, would make them traitors in the eyes of other Tlâńorē. I became acquainted with a number of them with the same goals as myself—comparing the old records from Tlâńor and Anθorâń with the world around us, trying to relearn what the ancients knew, and recover lost arts. Did you know there are people working on flying machines?" he said, dreamily.

"I saw a flying machine once," Saru said.

"What?" said the count and the doctor together.

"Well, the pieces of one, or what I was told had been one, scattered over a large area," Saru amended. "I was with one of the grandfathers of the tribe, and another boy, on a hunting trip. The other boy asked the grandfather if the machine could go to Haĵi, or Gron, if it weren't broken."

"What did he say?" asked Doctor Ĵetao.

"Hell, boy, you don't need a machine to go to a moon," Saru quoted. "I can tell you how to do that. First, you lift your left foot into the air. Then, you lift your right root higher than your left foot. Then you keep on doing that until you get where you want to go."

"But, Grandfather, if I lift both feet at once, I fall down!"

"Well, then, the old man said, that's the part you need to work on, and he winked at me," Saru said, grinning.

The count roared with laughter. The doctor, however, fixed a suspicious eye on the cornet, and said, "Saru, my friend, we were on a ship together for a year, and I never heard that story before."

"There are lots of things you haven't heard," Saru protested. "I was a banneret, for one thing, and had a lot of calls on my time."

"Moreover," Juho said, "that story has the classic elements of a peasant folk tale: the cranky old man, the credulous youth, and the narrator with whom the audience is supposed to identify."

"I don't know anything about literature," Saru said. "I'm just telling you what happened."

The count laughed again. "You were about to tell us where this map came from," he reminded Juho.

"Yes, Your Grace," Master Ĵetao said, still eyeing Saru doubtfully. "Well, after I'd been in Tlâńor for some time, and had made some friends among the intellectuals, one of them told me about a curious artifact in her possession."

"Ah ha!" Saru said, grinning. "Another conquest, Doctor?"

Master Ĵetao flushed. "Nothing like that," he said. "She's just a friend."

"I'll bet she is, too," Saru said to the proconsul. "It never ceases to amaze me how the good doctor is constantly being followed around by this bevy of women taking care of him, feeding him, and sleeping with him. And they don't get jealous of each other, and they remain his friends after he's done with them!"

"Ah," said the count. "That explains the behavior of the unmarried women here these past few days."

"Kaša said that this map was cut out of a wall with a knife by a soldier during the looting of Tlâńor," Juho said, ignoring the byplay pointedly. "When it was part of the wall, the dots moved," he said, tapping one of the dots on one of the ovals.

"Moved?!!" said Saru. "It isn't miracle enough that they shine?" He looked closer. "How could they move? They look painted on, or built in, or however the picture is done."

"Nevertheless, they moved," the doctor said, "until the display was cut out of the wall. Then they stopped moving, though they still glowed. At that point the looter abandoned it, and Kaša's father recovered it. When I realized what she was showing me, I begged her for the loan of it, and brought it here."

"All right, I'll bite," Saru said. "What do the circles and dots represent, and why did the dots move? I assume you don't know how they moved."

"Your assumption is correct," Master Ĵetao said. "Do you read Horiel, Saru?"

"Not a letter of it," Saru admitted cheerfully. "Nor the other kind, I forget what you call it."

"Iriel, not that there's any here," Juho said. "Very well, look down here. See this oval on the side of the map, that loops all over the westernmost part of Kantos? Can you make out what's written next to the dot near the bottom of the loop?"

Saru crouched down and looked. A squiggle that looked a little like a Q, another squiggle that looked like an N with the top flopped over, something very like a Ť, something else he'd never seen before, something else that looked like an R fallen on its back, another Q-like thing, two more N-like things.

"Not a clue," Saru said. "Doctor? If the writing's next to the dot, and the dot moved, did the writing move too?"

"Maybe," said Master Ĵetao. "But that bit of writing says Anθorâń. And this one says Haθ. This one, T́ebai. Sitašai. Tlâńor."

"That old fairy tale," Saru grumbled, as he rose to his feet, brushing off his uniform over his knees.

"Fairy tale, cornet?" the proconsul said. His tone of voice said, Explain yourself, young man.

"Sir," Saru said, "I know that you Râńē believe, or say you believe, that your cities used to fly in the ancient days. And that's fine, believe what you want."

"But we Girē are herders and breeders of riding animals. We bred a wild animal, too small and too slim to carry a man, into something that could run with a fully-armored knight on its back. You don't do that by believing any old story someone wants to tell you. You have to go by the facts, and use what actually works."

"I'm not sure I see your point," the count said.

"Sir, maybe the wrecks rusting here and there across the west were flying vehicles. And maybe the Râńē cities, and Anθorâń, and Tlâńor, used to fly. But I haven't seen them fly. You haven't seen them fly. No one's seen them fly."

"You're a skeptic," Doctor Ĵetao said. "But…"

"And if they flew," Saru went on, "How did they fly? Did they have giant wings, with giant feathers? What held them up? How were they steered? I don't believe in magic!"

"Skepticism is good," Master Ĵetao said. "But disbelief, like belief, has to accomodate the facts. There are too many texts, and too many artifacts, all taking for granted that the cities flew, and smaller vehicles between them."

"How?" Saru said.

"I don't know how," the doctor said. "Nor do I know why they stopped. Old sky maps show a very bright star above the north pole. It disappeared, and the cities had to come down, or crash like your grandfather's wreck."

"I've heard that story," Saru said. "I don't believe in astrology, either."

"Not astrology, but science we've lost," Juho told him. "The records speak of Herâk the pole star "going supernova", and emitting "radiation" and "energetic particles", causing "electromagnetic pulses". We don't know what those words mean—but civilization fell. Literally, for a few cities and countless vehicles."

"As fascinating as this is," Count Persu said sincerely, "perhaps you gentlemen could continue it later. I do have other matters awaiting my attention."

"Yes, sir," said Saru.

"Yes, Your Grace," Master Ĵetao said. "The point, Saru, is that we can account for every city shown on this map, except for this one." He tapped another dot. The legend next to it read:

"I, something, something, something, N?" Saru guessed.

"Provisionally Ištun," the doctor said. "Horiel doesn't distinguish between I and Î, or U and Û, so the vowels are uncertain. For that matter, it could be I-štun as easily as Iš-tun."

"Κtûn?" Saru said. "Like the song?"

"Song? What song?" Juho said.

"The children's round," Saru said. "Surely you know it? Oh," he said, looking at the two blank faces. "Is it a Girē thing only, then?"

"Perhaps you could sing it?" the count suggested. The doctor looked horrified.

"Sing it, sir? Me? You'd regret asking," Saru said. "I'm probably the only Girē who ever lived who can't sing. But in T́uliǹgrai it would go something like," he said, reciting:

"—Doctor, what did you do?" he said, breaking off with an amazed stare.

"Do?" Master Ĵetao said.

"The map, Doctor!" the proconsul said.

Master Ĵetao looked at the map, and gasped. It had changed. The blank white of the continent had given way to colored patterns indicating grasslands and forests; the two arms of the Sealed Mountains were shown, and the great rivers of Elarâń, the Raros and the Serońa; other rivers unknown to Râńē geographers could be seen in the south, and lakes, and mountains.

"I must have activated some control by accident," said the Master of the Phoenix, reaching out. Then he put his hands behind his back. "Your Grace, we must copy this before it disappears again!"

"At once," the count agreed. "Tell Senior Guardian Siθa to give you the services of his two best cartographers for as long as you need them, and tell him the order comes from me."

"On my way!" said the doctor, and sprang for the door.

"Meanwhile, cornet," said the proconsul.

"Sir!" said Saru.

"I believe your platoon is over strength?"

Uh oh, Saru thought.

"Sir, yes sir. I can explain. The remains of my banner naturally stayed together, and then the odds and sods we swept up in the fighting for the ships haven't been reassigned. There are a few bad actors I would be happy to lose, but mostly they're good men, sir. And they're just learning to work as a unit," he said desperately.

"No doubt," said the proconsul, "but what kind of unit? I count a good 65 men, cornet. That's nearly a banner!"

"If the proconsul would let me detach three or four useless bodies," Saru began.

"You'd still have three times the men you're supposed to," Count Persu said. "Either we need to split you up, or add more and make up a banner—someone else's banner, cornet."

"Yes, sir," Saru said, the only permissible answer. Cornets didn't command banners, legates did. His only hope of staying with the men was to be assigned to one of the platoons of the new banner.

"Meanwhile, however," the count continued, "I have a mission for your platoon. If you fail, we can try again with a regularly-constituted banner. If you succeed, it will go a long way towards proving the worth of your unit; and your own worth of another stripe, though I make no promises whatsoever."

"I'll do my best, sir!"

"So I'm told, so I'm told. You will take your platoon, with appropriate civilian supply and support, and you will locate and investigate the city of Κtûn. Master Ĵetao will accompany you and you will give weight to anything he says, but mark me, cornet, you are in charge. Is that clear?"

"Yes, sir!"

"You will take three T́ulańē scouts. You will be assisted by another cornet, who will be your second in command. Cornet Haθa is almost as highly recommended as yourself; try to get along with her."

"Her, sir?" said Saru, staring.

"That's right, cornet. We're adding our token woman to our misfit platoon, commanded by our token Girē, and sending the whole lot off to get lost, hoping they won't come back. Any questions?"

"Sir… No, sir."

"Good. Pick up your orders from the Senior Guardian on your way out, and tell him to send in the next victim. And good luck to you, cornet," he said, holding out his hand.

"Thank you, sir… I think," said Saru, son of Peta, shaking the proconsul's hand.

Panic and madness stalked the Galaxy; and it grew worse exponentially.

When Lara and ys fellows were designed, a single creature from the Long Time had appeared in the Galaxy. It passed through a Verē city, and people died by the thousands. Looking at it was enough to drive them insane, and the chaos that followed was lethal.

By the time Lara and ys companions were made, cosmologists had discovered that the monster was an explorer from another universe, very different from their own. For one thing, time passed at a different rate in each universe. Eborai Lapai and his wife went on a reconaissance mission to the other universe, and returned the same day with a grown son.

Long-Time incursions were frequent by the time Lara and ys siblings reached puberty. While they struggled to find their sexual identities, worlds were being torn apart. Not creatures of space and time as we know it, the extrauniversal explorers roamed without regard for whether they were in space, on the surface of a planet, striding through a star, wandering in the oceans of a living world, or meandering through the raging storms of a gas giant. Wherever they went, if there were living things to see them, insanity and death followed.

The lesser races of the Three Galaxies, especially those who had been so long at odds with the Verē in the Second Galaxy, took advantage of the situation. They discovered they could build ships piloted by arrays of computers, rather than having a sentient being look upon the monsters and lose its sanity. Decisions were made by people inside the ships, who only viewed schematics on the computers. Computer operations were enacted by consensus of three computers at a time; if one was corrupted, it was overruled, shut down, and another brought in from the standby array.

Ships like these could follow the Monsters of the Long Time around, and pounce on worlds of the Verē and their allies while they were wracked with madness. Verē ships, propelled and armed with telekinesis, using Verē telepathy for communications and Verē clairvoyance for navigation, were far superior to the attackers. But in the presence of the creatures, they were blind, or else full of gibbering lunatics; either way, helpless.

While Lara went through the agony of becoming female (and her siblings became neuter, female, or male like their Verē ancestors), and as their education and training proceeded, all the old scores, real and imagined, were settled. Eoverai, the home world, was destroyed. The Defenders of the Covenant were all slain; the Kaitempi, the Verē police and military, died too; the populations they were sworn to protect were murdered by the planetful. The Orthodox, who insisted the Powergiver had ordained their rule over lesser races, died; the Liberals, who wished to treat other species as equals, died; the old people, the young people, the birds and the fish and the great serpents in the oceans, all died.

Q'qq'k the Kaikhlir, one of their teachers, came to Lara and her siblings as they sat in the light of the cosmic discontinuity which both empowered and hid the artificial environment where they had been designed, made, and raised. All their faces turned to (him) as (he) entered.

(There's no point in describing Q'qq'k; (his) part in history, indeed (his) whole species' part, is all but over. I could describe (his) body, built like a hollow reed with flat ribbony arms and legs that coiled rather than bent as a man's does; (his) head, like a wide shallow bowl with another turned over and set on top of it, with eyes, ears, and other organs along the crack between the rims; I could even tell you why (he)'s referred to as (him)—but what would be the use?)

"Be welcome," said Lara; though female, she was the leader of the experimental creatures. Or at least she spoke for them, and among the Verē and their descendants, Speaker meant leader.

"Thank you," said the Kaikhlir. (He) sat, by coiling up (his) legs and resting (his) body on them, and coiling up (his) arms just below where they came out of the shell-shaped horny protrusions at the top of his body—never mind. (He) sat, and regarded the children thoughtfully with several of the eyes on the side of (his) head nearest them.

"The Verē are dead," (he) said without preamble. "The Tlâńē, the Ukkl, the Rulsad are dead. The Drē and the Kox have been destroyed, though they could dance unhurt at the heart of a star, and the Si will delight us no more. The Elihrai are extinct, and the Kaikhlir, though (I) yet speak to you. The allied races that come from other universes may live there still, but we dare not contact them, lest it lead the Monsters of the Long Time to them, and the killers who bay at their heels."

"So we're alone," Lara said. With the general body plan of a Verē, the skin and some of the sensory organs of a Tlâńē, she and her kind would have been strange to any of her ancestors. Her muscle efficiency came from the Ukkl, her increased capacity for absorbing and storing energy from the Drē, the Kox, and the Si. All of the allied races contributed genes to them, or genes were designed to emulate desired properties of races that didn't use DNA. They were a new kind, the ultimate achievement of Verē biological science. Ultimate, as in highest; ultimate, as in last.

"You're alone," Q'qq'k said. "You, alone, must decide what you will do with your lives. We your teacher/creators designed you with no purpose in mind. When the Monsters of the Long Time appeared, we thought you could explore where they came from; but that, now, is moot. We thought next that you could fight them; but what is there left to fight for? You must decide yourselves whether to try to blend into the new galactic society that will arise, flee to another galaxy or universe, or pursue some other goal you set for yourselves. We have created you the best we knew how, and we have taught you all we knew to teach. The future is yours, as the past was ours."

(He) uncoiled (himself) to (his) full height—does it matter whether that was one inch or thirty feet? "Let me just say," (he) told them, "that your creators are proud of you. And we love you, and we wish you well."

And (he) walked away; and they sat, and watched, with love and sorrow in their hearts. Knowing (him), knowing the Kaikhlir culture, they knew what would happen next.

"Listen!" said Vîd́a, one of the males. They all reached out with their group mind. Nothing, in all the universe, but themselves, and Q'qq'k and (his) sister-clones and their bud-husbands. Just a faint gabble at the edge of their mental "hearing", the buzzsaw static of alien minds.

"Blend in?" said Mera, one of the females. She held up her hand, three fingers and a thumb, exactly like a Verē's except that it was covered with the blue skin of a Tlâń.

"Protect?" said Culi, one of the neuters, bitterly. They listened as Q'qq'k and his pod went lovingly into oblivion together. One last tender thought for them, and then the experimentals were alone in the universe.

"Flee?!" said Êstâz, a male. He clenched his big fists and curled his lips in contempt.

Lara looked around the group. They were all looking at her, all waiting for her to say the word that no one else had said.

She didn't want to say it. Of all words, that one should never be said lightly or casually. But if she were Speaker, then she must speak for them. She knew what word they wanted her to say. And what other word was there, really, for them?

"Avenge," she said softly; the word fell into their waiting intent, and crystallized it, and decided the fate of the universe.

Saru pulled his mount to the side of the trail and stopped, half-twisting in his saddle, to watch his command approach. The mount, a grey-haired beast with overlapping circles of white, took this for a lapse of vigilance and tried to bite his knee off.

Saru had expected the move. Without taking his eyes off the platoon, he hit his charger across its sensitive snout with the braided leather quirt ready in his hand. "Su, su, Šary," he murmured. The beast squealed in pain and then hissed with anger. After a moment, it dropped its oversized deerlike head to the ground and began ripping up stalks of the tough, thick grass of the South.

Saru smiled a little, and twirled the quirt in his hand. The ugly, bad-tempered řobē did the same thing every time they stopped, and he whacked it in the same place and said the same thing to it. But show it another mount with an enemy riding it, or a foot soldier attacking its rider, and its viciousness became far less perfunctory. It was also fast as lightning when he gave it the signal to run. Its speed and its evil temper were the reason for its name; a šarē is a flying snake. But for now the ritual had satisfied its honor; he tucked the quirt in his belt.

As the proconsul had said, there were 65 men in Saru's "platoon", all headed south towards the most northern point of Κtûn's orbit on the Tlâńorai map. Each man in the platoon had a saddle, a rifled flintlock in his saddle holster, and a hooded cape rolled up behind the saddle, ready for one of the rain and thunder storms that burst out of nowhere in these endless flat southlands. Saddle bags carried each man's standard kit—powder cartridges wrapped in waxed paper, spare flints, rifle bullets, dried rations for a day or two, canteens of water—plus personal possessions: a book, a deck of cards, letters from home, candy, liquor, whatever the trooper valued and the regulations permitted, or the trooper thought he could hide. Each trooper's remount, the steed he rode on alternate days, carried his share of his squad's tent, cooking equipment, and even more spare flints, cartridges, and bullets.

One of the approaching figures left the column and came riding his way at a faster gait than the rest. That alone told Saru it had to be either his lead sergeant or the other officer of the command. The sun flashed off the metal cornet bar on the other's hat, and Saru smiled.

A moment later Cornet Haθa reined in and saluted smartly. She wore the same uniform the other soldiers did, but on her it was almost glamorous. The curves of her figure were neither lush nor boyishly slim, perhaps closer to the latter than the former, but very attractive. She rode the standard brown army mount with experienced ease. The round-crowned, wide-brimmed hat hid all of her close-trimmed yellow hair except a little behind delicate ears and on the back of a well-shaped neck. Like him, she wore a pistol on her belt in addition to the rifle borne by every member of the platoon. "Sir," she said as she saluted.

Saru returned her salute and said, "Good morning." They were still working out how to address each other. She could call him "sir", since he was senior to her, both in time in service and experience, and was in command of the expedition. Calling him by his name wasn't out of the question, either, since they were both cornets.

He, on the other hand, could address her as "My Lady," since she was the daughter of the late Baron of Haθ. Or he could address her by her given name, Deni, since they were the same rank. So far, neither had been so informal.

"Well, now that we've been under way for a month, what do you make of them?" he asked. At the same time he was wondering why he wasn't more attracted to her. She was fit, razor-witted, professional, fearless as far as he'd seen, with piercing blue eyes. Did her superior birth put him off so much? Or her three inches of height?

Now, despite her birth and her nominally equal rank, she hesitated an instant at his question. Then she said, "Sir, may I be frank?"

"By all means," he said. "And I can do without too many 'sirs' either, My Lady, just between the two of us, with no troopers or other officers to scandalize."

"Well…" she said. "No one's said it in so many words, but you're running a short banner here. You have an unofficial three-platoon organization, with corporals serving as platoon sergeants, Sergeant Paran doubling as your banneret, and you acting as a legate."

"And you serving as my staff of cornets," Saru agreed. "I haven't heard a question, yet?"

"No questions," the other cornet said. "It must have official approval, or two-thirds of the men would've been reassigned. Instead they add me, to serve as your staff. But how did this happen? And if the higher-ups really approve, where's the rest of your staff and the cornets for platoon leaders? For that matter, where are the promotions for you, Sergeant Paran, and—if that's not a sore point," she said belatedly.

"Heh," said Saru, baring his teeth. "Well, maybe a little. The thing is—and I hope this doesn't diminish your respect for my position—I never wanted to be an officer in the first place. So I'm not exactly counting the days until I get that second stripe."

"Not—? I don't understand," she said, frowning. Her tendrils curved forward in speculation, instead of standing straight up. The slight breeze rustled the long grass, rustled their mounts' manes, rustled his curly red hair and her blonde hair, short as it was; but didn't rustle those inquisitive tendrils.

"Eight ships sailed to Loraon," Saru said. "Every ship had a full crew, and a picked banner at full strength. The largest ship had the Êstâz, a sampling of his court, and the proconsul and his staff. The regimental tribunes, their staffs, the guardians of the two regiments, were deployed around the fleet. Everything was well planned and well organized. We had maps, tons of supplies, experienced sailors who'd been part of the way chasing the fish, known ports, and established contacts."

"You were there?" Deni said. "I lost my father and an uncle to that expedition."

"Two ships came back," Saru told her, holding up two fingers of his left hand, the little finger folded down and the thumb folded in. "Two; and they weren't exactly overmanned, either. We had the remains of four banners; the other ship had the pieces of the other four, and the survivors of the court. All told we had less than two banners of men, and the highest rank left was a tribune."

"What happened?" she said. "There's the official account, and then there's rumor… What chewed up so many men like that?"

"The Verē happened," Saru said, not seeing her; old blood was in his eyes. "I think we'd forgotten just how strong they were, despite the warning of the name; how bullheaded, how impossible to stop once started… The Êstâz said it best, I think. 'We fulfilled the prophecy—but no one ever said what the prophecy would cost us'."

"Ride with me," he said, pulling Šari's head up from the grass. "Keep your mount's head behind mine; if they come level, mine will take it as a challenge."

"Sir," she said quietly. The two cornets exchanged salutes with the sergeant at the head of the column, and rode back along its length.

"Loraon was a powder keg," Saru said, picking up the pace, "and we were the match. Once we said the name Êstâz, the fuse was lit. What did our intentions matter, once the fire reached the powder? Nothing."

"So…" Cornet Haθa said, "this platoon…"

"I was banneret of a full banner going into Loraon," Saru said harshly. "Paran was one of my platoon sergeants, but as soon as he'd lived down his most recent demotion for cause, he'd be a banneret again too, probably right after we got back."

"Cause?" said Deni.

"Fighting, drinking, and whoring," Saru said. "And not the first time, either. Maybe the first time he combined all three in one incident, and no doubt the biggest mess he'd ever made."

"Sergeant Paran?!" the other cornet said, staring. Her tendrils were bolt upright in shock. "Drinking? Whoring? I can see fighting," she said thoughtfully.

"The point is," Saru said, "we were a full banner, the regulation 85 common soldiers plus officers, when we left Kantos. When we got back, there were 32 of us. Five out of every eight were dead."

He held up his hand when she would have spoken; returned the salute of the corporal in charge of the squad taking care of the remounts, and spoke with him briefly. Five men seemed few to keep some 80 řobē under control, but řobē were herd animals, and most of these had been raised and trained with this unit. The corporal had the remounts dancing to his bidding, as the cornet did the men.

"Me, Paran, six corporals, 24 troopers," Saru said as they moved on.

"I see," Cornet Haθa said.

"Ten survivors from another banner: a sergeant, a corporal, eight troopers. Eleven—"

"Ten?! Out of 90-94 men, including the staff officers?"

"We were luckier than most," Saru said. "Eleven left of a third banner, one sergeant and ten troopers. Of a fourth banner, only one corporal and four troopers. Oh, and seven common seamen who decided they'd seen enough of deep water and exotic foreign ports."

"On ship with you, all the way back from Loraon?"

"With shattered morale, nothing to do, and with great gaping holes in our own ranks. It was either fit them into my banner, ignoring the fact that we had no cornets and no legates…"

"And how did that happen, sir? I heard…"

"They were all rounded up and slaughtered before the rest of us had a clue how the wind was blowing," Saru said harshly. "I know that includes the father and the uncle you mentioned, and I'm sorry. If it helps, the ones who weren't slain out of hand gave their lives to keep the Êstâz alive, and to get word to the rest of us."

"So you worked on the voyage back to keep your men from despairing over the worst defeat the army's ever known; and you turned them into a unit. That was very well done, if I may say so. No wonder the Êstâz made you an officer."

"Officer my balls!" Saru said, suddenly sounding like the common soldier he'd been so long. He pulled his mount up so hard it squealed and tried to bite his foot. He kicked it in the snout without bothering to pull out his quirt, and it hissed loudly.

"Fuck all officers," he went on, as the other cornet stopped too, startled at the raw savagery of his expression. Her mount danced nervously under her, unnerved by the rage of the other steed, and the pain and rage in Saru's voice. She soothed it to quivering stillness with the automatic life-long riding ability of the aristocracy.

"I didn't beat these men into line because I wanted to be an officer," he said, holding up a fist. It was a small fist, but the gesture wasn't even a little bit funny. "I never dreamed Command would be so stupid! I whipped these men into a unit thinking like a banneret, not a fucking officer!"

"There's not a man here who doesn't know that the best men of our banner—of all four of our banners!—were left in Loraon. That's why I accepted this stripe," Saru said, tapping the metal bar on his hat. "Not for me, but for the men who died holding the bridges between Lores and Tara. The men who died with Krahos spears in their guts at the doors of the Chamber of the Lie, before we shot the bastards down with volley fire! The men who were torn limb from limb by bare-handed Verē in the streets of Teřańa! The men who fought for the ships and were crushed between the hulls, or drowned, or devoured by serpents made mad by the blood in the harbor water!"

"So yes, this unit has some problems," Saru said, a little more quietly. "We are all survivors of Loraon, but some of the troops are too damned stupid to know what we owe our dead. But they're going to learn, and shape up, or by the Powergiver! They'll wish they had!"

"Amen," she said. He snorted, yanked his mount's head around again, and took off at right angles to the line of march, at a flat-out gallop, Šari's head stretched out low and mean, the Girē on his back lying down along his neck and urging him on, not a bit like a proper Army officer.

Laughter and low-voiced comments made Cornet Haθa leave off watching him, and rein around. The civilian sutlers, tinkers, and quacks had been a little too far away to hear what Saru had said, but they'd enjoyed the show anyway; and were enjoying the sight of him racing away.

"What the hell are you looking at?" said the Baron's daughter, and laid into them with a tongue like a sword.

"Now if we were a banner, this would be Third Platoon," Sergeant Paran said. "Probably the best unit we have, or at least the steadiest."

"Why, thank you, 'Banneret'," Corporal Mrada said, grinning. Deni would've thought he was too far away to hear Paran's comments as they passed, but apparently not. The sergeant held up one of his huge fists in semi-mock threat, and the grinning corporal threw him a salute in return.

The endless grass, stretching to the horizon under an immense sky full of mountains of clouds, was calculated to make anyone and anything seem small, especially Râńē, whose cultural mindset was still walled in by the Sealed Mountains. The platoon, the unofficial banner, rode south day after day and saw no change at all, as if they were ants crawling across a field.

On a human scale, however, Paran Anĝarat was huge, more like a šâigē, a giant ground sloth, than a man. At six foot ten inches, he was sixteen inches taller than Cornet Saru, and contained in his heavy frame enough bone and muscle to make two Sarus, with a good bit left over. Sergeant Paran had four mounts in the unit's herd, and switched his saddle twice a day. Even so, he walked a lot to wear out boots instead of animals.

His coloring marked him as much as his size. Just as most of the mounts were a uniform brown color and a uniform size, so the men were mostly around six feet tall with brown hair and brown eyes and brown skin. Paran was only part Râńē. His mother had been a Cundē slave, of a long line of Cundē slaves. His father had been a Râńē soldier during the sack of Mašad Anĝar—perhaps even the same soldier who married the ex-slave and raised her son, who knows? That son, now a man, had dark brown skin, like old leather, fine black hair, and black eyes. The tendrils rising from his temples were short and stubby, hardly more than fleshy horns, and his ears came to points that faced the rear. Though he served in the Êstâz's army, he was all Cundē in appearance.

"The steadiest, sergeant? I would have thought that would be your unit," Cornet Haθa said.

"No, because I have all the trouble makers and most of the sailors," Paran said. "Cornet Peta's son trusts me to break all our bad mounts and make proper riding animals out of them, so to speak. 'Third Platoon' has four squad leaders from our old banner, and two of them are actually corporals, not just troopers acting as corporals. Each of the squads has two troopers from our old banner as well, one trooper from Eagle Banner, and one trooper from Badger Banner. So everyone in Mrada's unit is an experienced troop, and three out of five have been together since recruitment."

"I see," said Deni. She pulled up where they could watch the central part of the column. "Give me an appraisal of this unit in the same terms, if you would."

"Yes, sir," said Paran; there were few females in the army of any rank, and command had decreed that females were to be treated and addressed as males. So "Yes, sir" was correct and "Yes, ma'am" was not.

"Acting-sergeant Ĵuha's unit is also pretty steady," Paran said. "You have Corporal Ĵuha himself, four squad leaders from our old banner, two corporals and two acting corporals, and one man in each squad as well. Each squad has one man from Eagle Banner that was, and one from Badger. So far, so good."

"But two of the squads are filled out with one man each from Raven Banner, and three of them are saddled with sailors; and that's not so good."

"Was there something wrong with Raven Banner, sergeant?" she asked. She scanned the column as they talked. Every item of equipment was present and in good repair, everything visible was stowed as regulations required. Every man rode with the odd combination of "riding at attention" that the army taught, and the boneless ease that countless hours in the saddle insisted upon—except for two, who sat their mounts like sacks of tubers.

"Nothing I ever heard of, sir," said Sergeant Paran. "But there were only five left! Powergiver knows, we all find ourselves looking for buddies who aren't here any more, but those guys are… um… haunted, if you follow me."

Deni smiled; she knew the sergeant had edited himself to keep from saying "fucking haunted" to her. But all she said was, "A corporal and four troopers, right? Why didn't our acting legate keep them together as a squad? Wouldn't that have been easier on them?"

"The cornet is pleased to jest," Paran said. "Of course it would've been easier, in the short run. But if they're going to stay in the army, if they're going to join our unit, best to separate them so they learn our ways, not cling to theirs; so they fit in with us, not with each other."

"And the sailors likewise?"

"Even more so," said Paran. "Those guys are worse than civilians. At least a civvie knows that he doesn't know anything, sir. These guys, we had to train them out of the navy way of doing things before we could even start to train them into the army way. And don't even get me started on their riding!"

"The rhythm of a deck and the rhythm of a řobē are very different," Cornet Haθa said diplomatically.

"Tell me about it," Paran groaned. "They're a little better now, but we had to tie them into their saddles the first time we were reviewed as a unit!"

"But the real problem is Trooper Suko there," he said, nodding towards a big, sloppy trooper ambling at the end of "Second Platoon's" part of the column. He lurched and bounced with every stride of his mount, and a hint of a rag tied around his head could be seen peeking out of his hat.

"A troublemaker?" Deni asked.

"Worse—an idiot. I don't know what happened to him; the other sailors tell different stories, and it was a long time ago. But whatever made that dished-in place in his skull, it left him only a little brighter than a canine. A domesticated canine, at that. Suko is apparently his actual name, but everyone on his old ship started calling him "Fool" long before we met him. Now he answers to Soko as readily as Suko."

"So why is he here?"

Paran pokered up. "You'll have to ask the other cornet for the answer to that, sir."

"All right," she said. "Now tell me about your 'platoon', sergeant."

"If the cornet will come with me," he said.

They kicked up their mounts and rode up the column. The component parts of the "banner" rode in a different order every day. One reason was fairness; the unit in front ate the least of the dust stirred up by the others, the unit in back the most. Another reason was to confound any potential attackers who might count on the pieces being in a particular order. Today, as it happened, the units were in textbook order: "First Platoon", "Second", "Third", the remounts, and the civilians. Cornet Haθa and Sergeant Paran rode to the front of the column, returned the salute of an expressionless Sergeant Rama, and rode a bit further and off to the left of the column (the east, since the column was headed south) where they couldn't be heard. The steady western wind helped, blowing sound from the column to them, not the other way around.

"What we might call 'First Platoon' is the only one led by an actual sergeant instead of an acting corporal," said the sergeant in question. "That gives him the most rank and the most experience of our 'platoon leaders', so he gets the hardest unit to handle."

"Hardest in what way?" Deni said.

"The most mixed, for one thing. Two troopers in each squad are from our old banner, well and good. The third man in first and third platoon is a Raven, and in second and fourth, a Badger. The fourth man in every platoon is a sailor, with all the awkwardness we spoke of."

"Then there are the personnel problems. Corporal Stâzo, the leader of fourth platoon," he said, pointing with his chin, "is the surviving corporal of the 'Ravens'. He seems to be a good man, but he's not quite one of us yet, and his ways aren't quite ours. And, as I said, haunted."

"The sailor in his platoon, Trooper Kraho, is one of our rotten eggs. Of all the men in this unit, don't ever let that one catch you alone. If he does, you may have to kill him. Good riddance if you do—but I don't like to think what he might do to you first. He doesn't look like much, with that skinny body, but he's tough as a snake, maybe as strong as I am, and he's totally bugfuck nuts, if you'll excuse my language, My Lady."

"Carry on," she said.

"The acting corporal in charge of 'Third Platoon' is Sergeant Seidu," Paran said. "He's not actually dangerous, except to unit morale, but he carries annoyance to stellar heights. He's a long-time soldier, and from casual acquaintance you'd think he was a top troop. His uniform is always just as it should be, and he's always there for assigned duties, and on time, too."

"But?"

"But if you actually observe him, you'll discover that he thinks his duty begins and ends with showing up," Sergeant Paran said in frustration. "Take guard duty, for instance. If you assign him to a post, and then watch him without him knowing, say at night, you'll find he picks a comfortable spot and just sits there the whole time."

"What?" said Cornet Haθa. "Sleeping on guard duty—"

"He doesn't sleep," Paran said hastily, holding up his hand, "he's just useless. Instead of patrolling his area, moving around so no infiltrator would know where he was, and checking on things in his area, he just sits there, staring into the fire if there is one. Reading. Playing cards. Every once in a great while—say once or twice in eight hours—he'll get up, stand in one spot facing the edges of his area for a little while, and then sit down again. I don't know what he thinks that accomplishes, exactly."

"Have you reported this?" Deni asked.

"The cornet knows," Paran said. "I've told him, and he's observed it himself, just checking, you know. He's talked to Sergeant Seidu about it."

"And?"

"Well, according to Seidu, I'm a liar. The specific times and dates, he hates to say it, but I have a tendency to make things up. I must have it in for him for some reason, the cornet knows how it is. Seidu's a threat to my position, both of us being sergeants, so I'm trying to make him look bad."

"And the cornet believes this?" Deni asked.

"No, thank the Powergiver. Saru knows he can believe everything I tell him. Even if he didn't know that, he's checked and seen it for himself. He just adds Seidu's lies to all the other things he doesn't do, or does wrong."

"Saru?" said Cornet Haθa.

Paran looked aggrieved. "Cornet Peta's son, I mean. But bear in mind, My Lady, we were both bannerets when we met, and we've been through hell together—or Lores-Tara, if there's a difference. He's saved my life, and I've saved his, and more than once. So if I slip from time to time, please excuse me."

"It's understandable," Deni smiled. "As long as you don't start calling me by name."

"Sir, without your explicit permission, I don't even know your given name—officially."

"So, if the cornet knows what Seidu is, why doesn't he get rid of him?" Deni said.

"We're in a funny position," Sergeant Paran said. "They'll either restore us to a banner, or break us up into platoons. Until they decide which, personnel actions are frozen."

"I see," said the cornet.

"Meanwhile, if Seidu thinks his rank means he should be in charge of one of our 'platoons', he can think again. No way, as long as I'm 'banneret', is he going to be infecting a whole 'platoon' with his attitudes and his ideas of duty. He stays in an acting corporal slot, in my 'platoon', where I can keep a close watch on him."

"Sergeant Rama's also in a corporal's position," Cornet Haθa noted.

"And it pisses him off no end. But Sergeant Rama and Corporal Jani are the other two trouble makers I need to keep under my thumb. They were the ranking survivors of 'Eagle', and the state those boys were in doesn't bear describing."

"You have to tell me something, sergeant."

"They're sadists, sir, and bullies. They like to inflict the maximum possible penalty for any infraction of any rule, whether it's the Army's, or something they made up themselves. They like to beat on people who aren't allowed to hit back. They like to abuse people with words who aren't allowed to reply. They steal things and then, when the theft is reported, they make everyone's lives hell until someone confesses just to stop it. If no one confesses, or the victim decides not to report it, they'll plant the stolen goods on someone and hold a 'surprise inspection' so they can 'discover' it. More stuff like that. An endless stream of stuff like that."

"There will be none of that in this unit," Cornet Haθa said firmly.

Paran grinned. "That's what the acting legate said, sir; word for word, I swear. Rama and Jani are each in charge of a different squad of my platoon, and all the troopers from Eagle are in other 'platoons'. If Rama and Jani try their old tricks, they'll find our men, and the men from Badger and Raven, won't put up with it. The word is out to complain if anything out of line happens."

"That seriously undermines their authority with their squads, of course," Deni noted.

Paran snorted. "If they want authority, let them show they deserve it. I won't countenance empty gripes, say from the sailors, who may not understand what's a legal order and what isn't. But Rama's and Jani's games are over."

"Some would say you're babying the troops," Deni said.

"Sir, some would. But in this unit, banner or platoon or whatever the hell it is, we're professionals. A professional will point his rifle when he's told to point it, and pull the trigger when he's told to pull it, wounded, sick, in bad weather, under enemy fire, outnumbered, whatever—because he's a professional. He takes the pay, he does the job. That doesn't mean that wounds, illness, bad weather, and so forth are good things."

"But the men are expected to endure these things, sergeant," Deni said, watching him.

"If they're unavoidable, sure. But the Army isn't a punishment detail. The army's job is to fight the kingdom's enemies. It's not a home for bewildered sailors, or a source of new victims for psychopaths in uniform. It's not an easy living for slugs too lazy to work. And it sure as hell isn't a school where bullies and sadists can enjoy themselves while neglecting their real duties!"

"Very good, Sergeant Paran," the cornet said. "I agree with every word. Now tell me something, if you would."

"Sir?"

"You've talked about men from the old Eagle Banner, the former Badger Banner, and the now-defunct Raven Banner. But you haven't said what this unit calls itself."

"Sir," Paran said, poker-faced, "the unit has no present official designation, being unattached to any command except Sixth Army itself."

"Don't even try that one," Deni said. "I wasn't talking about so-and-so platoon, of such-and-such banner, regiment, and brigade. What was the banner's totem, sergeant? What flag did you show?"

"Sir!" said Paran, trusting his instincts. The totems were unofficial, but they were what mattered to the men. "This was Orkē Banner, sir! And when—not if!—we're a banner again, if some other banner has taken to using that name, there will be fists flying, sir!"

"I'm aware of the custom, sergeant. At ease. Long live Orkē Banner!"

"Long live, sir!"

"And thanks for the briefing, banneret," Cornet Haθa said. She gathered the reins of her steed and urged it into motion to rejoin the column.

Late in the afternoon Paran picked a spot for the night's camp, Saru approved it, and the day's ride ended.

That didn't mean the work was over. Far from it! When the column halted, the men jumped off their steeds and ran to their tasks. Their mounts were tended and added to the unit's herd. A stake was planted in the middle of the camp-to-be, and the same distance measured off to north, south, west, and east. The troops went to work digging ditches too wide to jump and too deep to climb into or out of easily, with sharpened wooden stakes in the bottom and inside wall of the ditches. The dirt from the ditches was piled into walls just inside, and packed hard.

Saru's tent went up in the center of camp, where the roads running in from the gates met, with Deni's tent behind it, just to the north. The dozen civilians were suffered to pitch their tents on either side of the west road and the east road. First Platoon pitched its four squad tents along the center of the back, or north wall, with Sergeant Paran's tent just inside the back gate. Second Platoon's tents ran inside the south wall from the southwest corner to the main gate, and Third Platoon's tents ran from the other side of the main gate to the southeast corner. Two picket lines of twenty mounts each stretched out parallel to the west road between it and Second Platoon, two more between the east road and Third Platoon, two more between the west road and the back wall, and the last two between the back wall and the east road. Sentinels were posted at all four gates and all four corners; the squad leaders for the two squads pulling that duty roved around the perimeter on no set pattern.

It was a lot of work, but every command in the field did it, every day. The resurrection of civilization in Kantos had begun with Êstâz's troops relieving civilian populations besieged in impenetrable cities by howling savages. The savages had been broken, and driven out of Elarâń, which then became one huge fortress behind the Sealed Mountains, with Sitašai as its main gate. When the armies marched out of that gate at last, the habit of fighting from fortified positions was practically written in their DNA. From camps like this one they linked up with Anθorâń, squeezed the Girē into submission, marched on Cunda and reduced it, even, finally, reversed all their long practice and took Mašad Anĝar and Tlâńor from their defenders. Not prepare a camp for the night? Even Sergeant Seidu did his part, if not an inch or an ounce more.

The squad detached as hunters returned in a group, having cut two young calves out of a herd of vadē and butchered them. The bison meat and organs, and the fat from the humps, were divided among the pots of all the squads and the civilians, who provided spices and seasonings. The řobē droppings from a few days before, now completely dry, were piled up for fuel. Dry grass was set blazing with sparks from flints that couldn't be used in the rifles any more, either because constant sharpening had made them too small, or because they'd broken. As the fires began to catch, the three T́ulańē scouts, Herâk, Surâk, and Pâka by "name", appeared in the middle of camp without the sentinels having seen them coming. While the corporals of the guard gave their men a perfunctory chewing-out for not having managed the impossible, and the guards stoically endured it, the bare-chested scouts handed over a brace of beitē, grassland woodchucks; a grass net full of pheasants; and an entire penařobē, wild relative of the řobē, eviscerated but otherwise whole. This too was divided among all the cook fires, while the scouts withdrew to the nearby stream to clean up. T́ulańē didn't eat with, or in the sight of non-T́ulańē; nor would they sleep in the camp.

Master Ĵetao came riding in as the evening drew on, a dashing figure with his fine riding and his non-uniform garb, today a bright green tunic over a yellow shirt over a grey robe with black bands at the bottom hem and wrists. The wide straw hat on his head had a high flat crown, totally different from the low round crown of the soldiers' hats, and held a red hatband, into which he'd tucked a yellow prairie flower. Trailed by the two troopers he'd requested for assistance, he sprang from his mount at the back gate and greeted the grinning guard there before addressing his helpers.

"Be careful with those baskets," he cried to Trooper Korva. "I swear that's an entirely new species of plant that I haven't seen in Anθorâń's library, nor Tlâńor's either. You remember how I showed you to press it?"

"I remember, doctor."

"Good man! Do it right and I'll name it after you, see if I won't."

"Řo-Řobē," said Trooper Suko.

"Yes, you may tend the řobē, Trooper Suko," the doctor said. "Thank you for your work today. You were a big help." He watched the ex-sailor stumbling away with the mounts in tow, and shook his head sadly.

Saru looked up sharply as the fading southern light was blocked momentarily by a body entering his tent without permission or even being announced, then relaxed when he saw it was Master Ĵetao. "Good afternoon, Juho," he said.

"Good evening, rather," the master said. "Ehiu, it's dark as a cave in here, Saru."

"I hadn't noticed; but you're right. Guard, there!" he called.

"Sir!" said one of the two troopers outside the tent, coming in and standing at attention.

"Light my lanterns, please," Saru said.

"Yes, sir," said the guard. He handed his rifle to the other guard outside the entrance, took the two candle lanterns from the rope between two side poles, and left at a run.

"How was your day, doctor?" the cornet asked. "Did you find what you hoped?"

"I did, actually," Master Ĵetao said. "That line of greenery we passed yesterday marked the course of a small stream, just as you thought it might; and I think I may have found a new species of diže growing there."

"Diže, doctor?"

"A medicinal plant; its leaves are good for pain, and the root relaxes constricted blood vessels. At least, the species we know."

The sentinel returned with the candle lanterns. Designed to hang overhead, they had panes of clear horn to protect the candle from wind and the tent from the candle flame, and polished brass backs to magnify and reflect the candle light. The cornet thanked the guard, who went back to his duty; the doctor hung the lanterns in the loops of a rope between center and side poles, where their light shown on the camp table next to the center pole.

Presently Sergeant Paran came by with two troopers carrying dinner for three—cuts of meat, stew, fresh biscuits, salad of wild greens. The sergeant and the doctor traded the old jokes of men who are fond of each other but very different. Paran pretended to discover a stork in the tent and requested Saru's permission to bag it for the stew pot, while Juho asked how long Saru expected his poor wild city mutt to keep up with the riders on a long mounted expedition. Then Paran and the troopers left, grinning. Cornet Haθa came in as they departed, and the two cornets and the doctor had a good supper with pleasant conversation while the stars began their nightly dance in the endless southern sky.

The galaxies rejoiced! The monsters were all dead, and the future looked bright and rosy.

Well, the Second Galaxy rejoiced, anyway. It was true that the Ukkl had never claimed the ownership of the Whirlpool Galaxy the way the Verē hard-liners had the Second; indeed they'd fought the Verē to keep them out. When the war between the two races ground to a halt, the Covenant that resulted gave the galaxy to the Ukkl—but it was just a piece of paper that kept the Verē away, as far as the Ukkl and the other races of that galaxy were concerned. And the Kaikhlir signed on behalf of all the races of the Third Galaxy without having to fight, due to the Ukkl example.

OK, then, the Second Galaxy rejoices that the Verē, the Drē, the Tlâńē, and the rest of the monsters are all dead. But make the rejoicing quick, because there are a lot of serious problems we have to deal with. None of us ever had anything in common except opposing the Verē, and wars are starting over worlds the Verē claimed as their own. Not to mention the disruption of travel and trade by the utter destruction of worlds that were important crossroads for both. And didn't anyone ever realize how much of our technology was Verē hand-me-downs? Or how much of our science depended on things the Verē discovered and passed on?

Can we even get to other galaxies, or the far side of our own, without Verē teles? What's the farthest place you've heard from, since they were killed? Hey, that medicine derives from a plant that grows on a Rulsad world—is there an equivalent in this universe? Well, can we synthesize the active ingredient? What do you mean, you don't know what it is?

Light of Asteroch, I regret to report that the population of your world of Ishchtassh has been reduced by nine-tenths. The sacred blossoms will rot in the fields, for lack of hands to pick them. Plague, Your Radiance? Indeed no, it was the creatures from the Slow Universe. Three of them walked across the Aspirant World, and your people died by the millions. Fight them? How, Your Radiance? Yes, we won several worlds following them, but we can't talk to them, Eye of God. Yes, they're still here…

Wars, diseases, technology fallen apart, science ground to a halt, contact with other galaxies and other universes cut off, and still the Monsters of the Long Time prowl…

What was it we were celebrating, again?

"Âqquq niquq Volâk niquk ha!"

The cry was as loud and shrill as a woman's scream. Saru sat bolt upright in his sleeping bag and grabbed his pistol by instinct. Then he stopped and listened for a moment.

"Âqquq niquq Volâk niquk ha!"

Saru threw himself to his feet and out the door of his tent, wearing nothing but his robe, his pistol in his right hand. He cocked it while he swept the tent flaps aside with the powder horn in his left. "At ease!" he said to the startled sentries, before they could finish presenting arms, and poured powder into the priming pan from the horn.

"Ha âqquq niquq! Ha niquk Volâk!"

The shriek came from the north. Saru hurried around his tent and peered in that direction. All he saw was Cornet Haθa looking the same way. She, too, was wearing only her robe, and holding a cocked pistol. Her left hand was cupped over the pan of the level weapon to protect the powder from wind and rain while she listened intently.

There was nothing to hear but the predawn wind rustling the long grass. A few stars still shone, mostly in the black western sky; but the eastern sky was dark blue and starless, with a spark on the horizon promising the day.

Master Ĵetao came strolling up the west road of the camp, bareheaded but wrapped in his black cloak. "That's it, I believe," he said cheerfully. "Marvelous, wasn't it?"

"What was it?" Saru said, feeling foolish in the face of the doctor's unconcern. He shivered. The dawn air, he suddenly noticed, was very cold.

"One of the T́ulańē praying the sun up," Juho said. "Or 'praying' may not be the right word, 'celebrating' might be more accurate."

Indeed Vol was breaking free of the horizon as they stood there, and the sky was brightening moment by moment. Birds began to caw, chirp, peep, and otherwise sing in their various ways all around the camp.

"So why haven't we heard this before?" Saru demanded. He tilted his pistol and wasted the priming charge into the wind, balancing the waste in a second's unconscious calculation of the expedition's powder, the fact that no inhabitants had been encountered so far, and the lack of time to dry the powder before they set out for the morning.

"It must be the first time one of them's been close enough to the camp for us to hear him, when the sun came up," the doctor said. "The sources say every one of them hails the sunrise, wherever he is, every morning."

"I wonder just how far from camp they go at night," Saru speculated. As he spoke, Cornet Haθa turned to go back into her tent, and saw them standing there. She dumped the priming charge she'd been protecting, switched the pistol to her left hand, and saluted Saru with her now-empty right, gloriously unconcerned with the way the wind rustled her robe, and molded it to the curves of her body. Saru hastily switched his own pistol, returned the salute, and indicated with a jerk of his head that he was going into his tent to dress. She nodded, and turned to do the same. Master Ĵetao, unoccupied by military niceties, stood there in his warm cape and watched her until she disappeared into her tent. Then he sighed, and went back to his own.

Perhaps half an hour later, fully dressed now in an orange tunic, a white shirt, and a dark blue robe with white hem and wrist bands, the doctor entered Saru's tent with a nod to the sentries, doffing his high-crowned straw hat as he did so; the hat's band was the same color as his tunic today, with a head of pampas grass adding a jaunty note.

"Good stars, Juho!" Saru said. "How many outfits did you bring, anyway?" He was sipping a cup of blackbrew, made from the black-eyed bean which had survived the fall of civilization only in the greenhouses of Loraon. All of the Loraon-expedition survivors were addicted to the stuff, so it was fortunate they'd found ways to bring some of the plants back with them. In Kantos it could grow outdoors, and needed very little care.

"Not a lot, really," the doctor said. "I brought my own mounts, specimen baskets, a few scientific instruments, and so forth. If I also brought some clothes, it doesn't add much to the load. I just made sure that none of the tunics clash with any of the shirts, and none of the shirts clash with any of the robes. With five of each, that gives me 125 combinations, and one set doesn't have to be packed because I'm wearing it."

"As always, doctor, I see you've planned carefully," the cornet said drily.

"I think so," Master Ĵetao said. "My hat is plain straw, so it goes with everything; and my boots, belt, pouch, even my saddle bags and instrument cases, are all black leather."

"You're aware that every soldier in camp, from me to the troopers, has exactly two uniforms, including the one he's wearing?" Saru pointed out.

"My dear Saru," said the doctor, "that's hardly my fault."

The cornet laughed. "I give up," he said. "Have you eaten? Or would you like a cup of blackbrew?"

The doctor's nose twitched at the aroma rising from Saru's cup, but he said, "I don't drink blackbrew any more, my friend."

Saru looked at him in surprise, his cup halfway to his lips. "Don't drink it! Why not? And for that matter," he said, closing his eyes and breathing in the steam from his cup, "how?"

"Let me answer with a syllogism," said Master Ĵetao, folding his arms. "Point the first, blackbrew has a strong and distinctive aroma."

"Indeed it does," Saru agreed, taking a sip from his cup.

"Point the second, those who drink blackbrew every day, smell of it. The aroma, shall we say, comes out of their pores, and their breath smells strongly of it."

"Yes, I remember noticing the way the Krahosē smelled, when we first arrived," Saru said. "After a while, of course, I got used to it."

"Point the third, people who do not habitually drink blackbrew may find its aroma, and the smell of persons who drink it, unpleasant. Or even offensive."

"Um… It's been a long time now, but… Yes, I guess that could be…"

"Point the fourth," Master Ĵetao said with a smirk, "Cornet Haθa has never been to Loraon, and doesn't drink blackbrew."

Saru stopped with his cup halfway to his lips and stared at his friend open-mouthed. "Why, you conniving bastard," he said.

"Me?" said Juho, spreading his hands. "What have I done?"

"Exactly when were you planning to tell me all this?" said Saru. "At the wedding, perhaps?"

"I don't know what you're talking about," Master Ĵetao said, his lips twitching. "As for telling you anything, you've known all these facts as long as I have. Should I insult your intelligence by assuming that you're incapable of drawing obvious conclusions?"

"And it isn't even 'just' Cornet Haθa," Saru said mournfully, gazing at the half-full cup in his hand. "It's every woman in the Kingdom, unless she has no sense of smell, happens not to mind the odor, or chooses to become a blackbrew drinker herself!"

"You could get the whole Kingdom habituated, perhaps," Juho said. "If the Êstâz began drinking it, the court would follow; and where the court goes, the people follow."

"He can't stand the stuff," Saru said. "Says it reminds him too much of Loraon. Damn!"

Saru stepped out the door of his tent and flung the rest of the blackbrew in his cup into the road. "Sound Break Camp," he snapped to the sentry.

"Now, sir?" said the sentry; it was only half way through the breakfast time the expedition had been observing.

"Yes, now, damn your eyes!" Saru snarled. The sentry saluted, and raised his horn to his lips. As the loud, low notes blasted out over camp, men reacted in shock as far as the eye could see. In seconds there was hasty activity everywhere.